A Monumental Alentejo Wine

Herdade do Esporão’s story told through three of its iconic winemakers

The multitude of historic castles, hilltop forts and towers scattering the Portuguese countryside weren’t just built for fun.

From the Lucitani Celts and their castros through the Moors, the re-conquistadors and Knights Templar, to the centuries of defence on the long border with Spain, these fortifications are monuments to wars gone by.

But among them stands one tower erected as an expression of new found power and to symbolise the start of a new family lineage – a new beginning.

The Esporão Tower was built between 1457 and 1490 by a nobleman from a high-society family with royal connections and was used to plant a flag of possession and intent.

And centuries later Esporão has been at the heart of something decades-long, big and ambitious – a symbol of change and of new beginnings which gave rise to a new lineage, or generation, of Portuguese winemakers.

The fifteenth century knight Álvaro Mendes de Vasconcelos was a man with big ambitions – much like José Roquette, the Portuguese banker and businessman who bought the Esporão wine estate with his partner Joaquim Bandeira in 1973.

A year later they lost it to the revolution and it was only returned on the condition the grapes went to the local cooperative.

It wasn’t until the 1980s when what is now one of Alentejo’s most widely known wineries began re-planting, modernising and producing great wine.

“It was something incredible,” says Luís Duarte, who joined Esporão in 1987 straight out of the very first oenology class at the University of Trás-os-Montes close to the Douro in Vila Real. That marked the beginning of Portugal’s modern approach to winemaking.

“When I arrived we started building one of the most famous and beautiful wineries in Portugal, but it was very difficult to build in three months: below the ground with big tunnels – it was crazy,” Luís said.

A few years later he was joined by David Baverstock – an Australian winemaker who by then had met his Portuguese wife and after spending harvests, or “vintages” abroad had been in Portugal for a decade.

“The winery was brilliant – it was really well designed. I mean, what they did to this hillside was insane,” said David who only recently left Esporão after 30 years.

“They carved out the middle of it, they put in the concrete structures, and then they put the earth back on top again. Most of the storage tanks were underground...and everything was done by gravity.”

Deep below the ground it’s as impressive today with its refreshingly cool temperature despite the intense Alentejo heat, and the cavernous cellar space resembles a cathedral or a subterranean football field.

“Or a metropolitan station – an underground station?” suggested Sandra Alves, the third winemaker we spoke to for this history lesson, and who gave us a tour of the iconic winery.

It’s a great place to visit in Reguengos de Monsaraz, and well set up for visitors, with tours, tastings and restaurant with a Michelin star and a Michelin green star for sustainability.

José Roquette’s son João took over the running of the winery and made another ambitious step in the 2000s when he decided the whole estate should become organic.

With more than 600ha of vines, Esporão is now one of the top ten largest organic vineyards in the world.

In the cellar, thousands of bottles are racked from floor to ceiling and a futuristic tasting table sits in the middle which resembles a wooden sculpture of the Starship Enterprise.

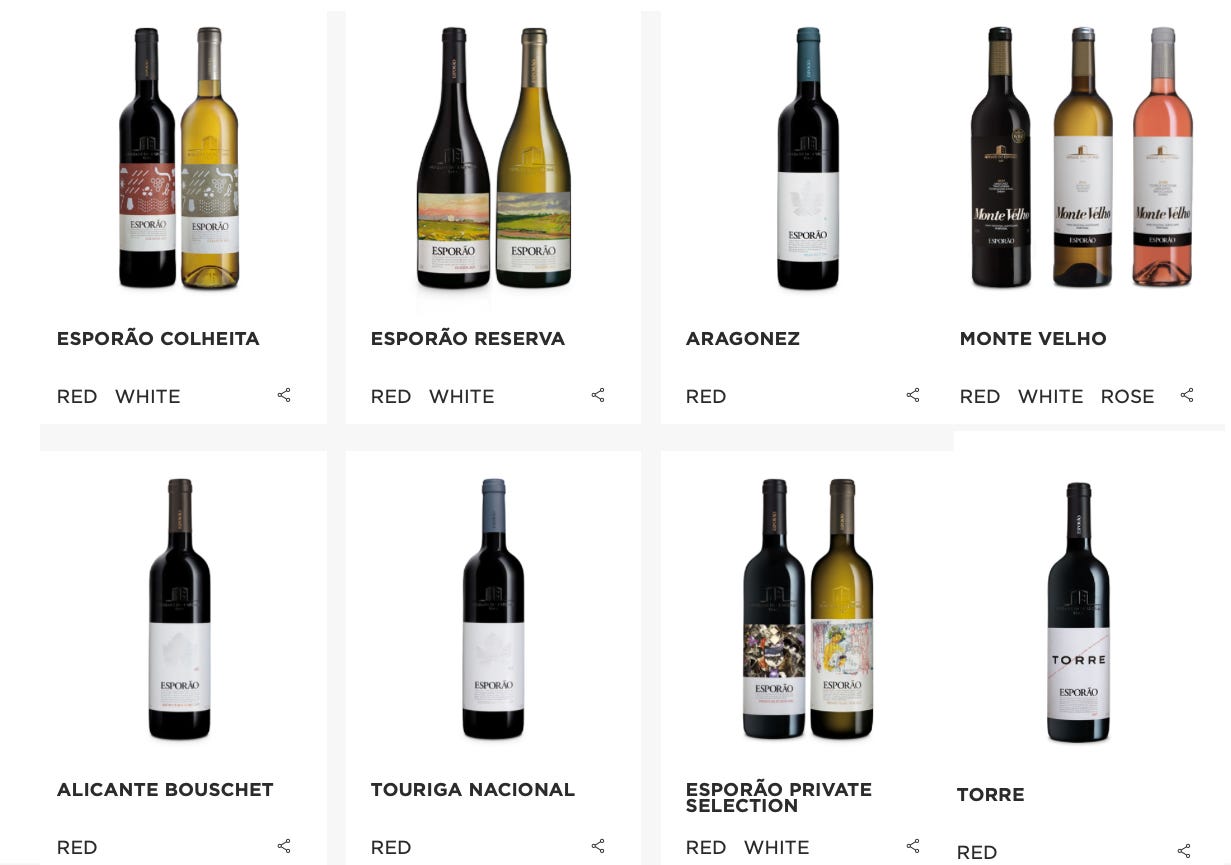

Esporão produces a whole range of wines in Alentejo from the famous mass-market Monte Velho to the Reservas, Private Selection bottles and the “Torre” wines which are only produced in exceptional years.

Named after the famous tower, they have only been released from the 2004, 2007, 2011 and 2017 vintages, picked up a lot of points from wine critics and sell for hundreds of euros.

But the tower appears on all the wine bottle and the olive oil the estate also produces – a symbol of the now restored national monument, as Esporão’s website puts it: “having now regained its former splendour and importance.”

And that’s a good allegory for the fortunes of Portugal and Alentejo’s wines that follow the story of Esporão and our three winemakers.

“In the early days, when I first came over here, it was very hit or miss,” said David Baverstock.

“You’d buy red wine in a supermarket and it was maybe a little bit fizzy, a bit gassy or dirty or something because the malolactic fermentation hadn't been properly controlled. There were a lot of basic winemaking faults back then.

“A lot of it was just sort of handed down from generation to generation, there wasn't a lot known about the grape varieties, and suddenly they realised they've got these 250 indigenous grape varieties that no other country in the world has.”

Portugal’s entry into the then European Economic Community (EEC) in 1986 made a huge difference.

“The money just poured in: the roads got better, there was money for vineyards and wineries,” added David.

And the money was put to good use – investment in research, stainless steel tanks, temperature-controlled fermentation, university courses and the knowledge to grow the right grapes in the right places.

“We started to follow the ideas that David brought from Australia – from the new world,” said Luís Duarte, of the time when Esporão started to experiment.

“When this happened it was very important for Portugal because it added a lot of people with knowledge of the new technology,” which Luís said led to increased confidence from investors that Portuguese wine was a good place to spend their money.

“We belong to the old world of wine but we are very new in terms of our knowledge,” especially when compared to places like France that didn’t suffer the disruption of dictatorship.

During the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar and the regime’s “Estado Novo” or “New State” plan, centuries of wine history in Alentejo were wiped out when vines were ripped out to be replaced by cereals, however the climate in the region was never suitable for grains.

But for the last 30 years or so the Alentejo – with its sunshine, rich soils and many microclimates – has emerged again as the home of amazing wines.

The region is now the biggest producer for the domestic market. Unlike the narrow terraced hillsides of the Douro, the wide rolling hills provide plenty of space for more vineyards and mechanised harvesting.

“This region makes fantastic wines, has this fantastic potential, can mechanise and has a consistent quality every year,” said Luís Duarte.

“The generalisation is still that Alentejo can produce very, very easy drinking commercial style wines in quite big volumes,” added David Baverstock.

“There's a general stereotype, particularly with the reds, that they're going to be a bit on the heavier side, they're going to have soft tannins...a fair bit of alcohol and they're going to be quite ripe fruit flavour.”

But he explained winemakers are now moving towards making fresher and more elegant wines which the different terroirs and better understanding of Portuguese grapes encourages.

“Alentejo is really drinkable wine, a really intense wine – at some stage really fruity. Almost exotic for an American market, but at the same time, it's gastronomic as well,” said Sandra Alves, looking out over the parched soil, the cork oak trees and the big skies.

“All the intensity that you see all around you...all this yellow and green and blue – I think the wines show these colours, all this intensity is everything very powerful, very intense, very unique.

“I would say that you need to taste to understand and you need to come here as well to understand what I'm talking about.”

David's comment "winemakers are now moving towards making fresher and more elegant wines which the different terroirs and better understanding of Portuguese grapes encourages" reminds me of the trend now in the Riverland Wine Region in South Australia. This is a hot region which has for decades produced masses of bulk wine, but is now home to innovative winemakers making elegant wines, some from Portuguese varieties such as Arinto.