The Romans were making wine in clay amphora pots across their Empire two thousand years ago, and in one small town in rural Portugal they’ve been making it the same way ever since.

Vila de Frades, or friars’ town, takes its name from the monks who spent centuries producing communion wine at the nearby São Cucufate monastery which was built on the ruins of a Roman villa.

Thanks to the rising popularity of natural wines and with the help of a great story, Vila de Frades in Alentejo now finds itself at the centre of a Roman-style wine revival.

Talha wines, as they are called in Portugal, have their own official classification and the strict rule is the wine must stay in the clay pot until St Martin’s Day...on November 11th.

That’s why at this time of year they are literally celebrating in the streets and singing about it in the taberna taverns.

Teresa Caeiro, 27, gave up a promising career in diamond mining after falling in love and doing something unusual for rural Portugal: deciding to come back home to make wine with her grandfather.

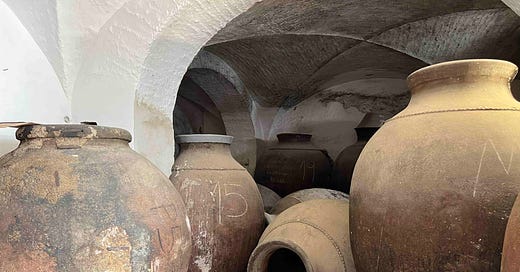

Fifty talha pots are propped up under a beautiful vaulted ceiling in her small Gerações de Talha (Generations of Talha) winery which has stood on the main street of Vila de Frades for at least 250 years.

There are wineries scattered all around this small town and even a modern talha interpretive centre with interactive exhibits, snazzy videos and a lot of information.

The family home is upstairs where Teresa found a connection to wine as a little girl: “When I was a baby I remember the sound of the wine filtering out of the talha. It’s amazing – such a fantastic sound – like “ahhhhhh.”

And on a recent St Martin’s Day visit we were able to hear it for ourselves.

At 3pm sharp her husband João started hammering a wooden tap into a cork hole near the bottom of the clay pot while Teresa went live on Instagram to share the moment with her followers.

A few seconds later came the wonderful trickling sound of young wine draining into a bowl: the sound of autumn in Alentejo and a taste that dates back thousands of years.

I did a radio version of this story for the BBC this week and have added it here so you can hear the people I’m writing about, immerse yourself in some amazing singing…and listen to that wonderful trickling sound:

Traditionally the grapes used for making talha wines are a “field blend” – a mixture of the many indigenous Portuguese grapes all grown and harvested together.

“We have more than ten different varieties of red and white grapes such as Alfrocheiro, Aragonez, Trincadeira and Touriga Nacional, but only my grandfather knows which is which,” said Teresa.

It was historically a hedge against the weather – in different years and conditions different grapes do better and harvest time is always when some grapes are over ripe, some are green, but most of the fruit is ripe and ready.

The grapes are pressed and most of the fruit, skins, pips and even some of the stems are thrown into the amphora together.

Nothing is added – natural yeasts from the grapes start the fermentation and the solid materials form into a cap which is called “the mother.”

Three times a day for the three weeks of fermentation, the cap has to be punched through with a wooden stick to prevent carbon dioxide from building up and causing the talha to explode.

It’s never happened to Teresa, but most talha wineries have floors sloping towards a hole in the middle of the room with an empty amphora underneath – just in case.

Once fermentation ends, the mother drops to the bottom of the vessel and creates a natural filter which the wine emerges through two months later fresh, clear and ready to drink or be transferred into something else to mature.

“We are six grandchildren. I am the only girl and I am the only one studying, so when he saw I wanted to work with wine he said ‘oh my God! What are you doing with your life?’ but really he loves what I am doing and just doesn’t say so,” Teresa explained.

She studied oenology, learned the traditional techniques from her grandfather and now the whole family is involved in the making, the bottling, the labelling and the selling, but what’s she like to work with?

“Muito dificil,” very difficult, laughed Arlindo Ruivo, who has made wine like this for fifty years and his experience sometimes clashes with what his granddaughter has learned from books.

“I’m glad the young generation don’t want to lose the traditional roots of the winemaking and want to take it further, and so the older generation are giving them a kick in the backside.”

Teresa likes to harvest the field blend of grapes a little earlier than her grandfather so they are more acidic, lower in alcohol and make wines that are more attractive to younger drinkers.

He likes the more earthy, heavier wines that are more typical of talha and so they have two brands: Farrapo which is the more traditional, named after a peasant’s shawl and NaTalha which sells in Lisbon’s natural wine bars.

They also make a special Prof Arlindo Red which is the best of their best.

A dozen wineries opened their doors to visitors this year as Teresa and another new-generation winemaker, Ruben Honrado, organised the town’s first festival for the increasing number of wine tourists taking a talha pilgrimage

“I love the idea of natural, old wine, so we’re here to drink as much as we possibly can,” laughed Tina Dameron, an American now living in Portugal with her husband Bob who came after reading about the hastily arranged festival.

Ruben has seen an uptick in the number of visitors to the beautiful old Honrado winery and next door to his family’s famous restaurant País das Uvas (Grape Country) for traditional Alentejo foods like black pork cheeks and bread-based accompanying dishes.

The festival was designed to spread visitors around town, but the new festival’s €45 fee for a tasting glass necklace and bottomless samples was considered a bit steep by the locals.

“It’s been tough because whether we like it we are in a small village and people are still a little bit traditional and are used to seeing vinho de talha as part of their culture and easy to access,” said Ruben Honrado.

“But I think it’s a matter of shaping minds. The money is being shared with the community and in the long run people will understand it’s good for everyone: hotels are full, restaurants are full, wine cellars are full, the village is alive and it’s fun. It’s a win-win, win-win, win-win for everyone.”

In the more traditional adega wineries and tabernas, small groups of men were spontaneously bursting into song.

We heard distant singing coming from a seemingly abandoned street and stumbled across Adega Justino Damas. Justino invited us in for snack, a chat and to hear some traditional tunes.

Cante Alentejano is the polyphonic style of Alentejo, performed by small wine-fuelled male choirs – groups of friends following the St Martin’s Day traditions.

The singing style was given Intangible Cultural Heritage status by UNESCO and the mayor of Vidiguera municipality is campaigning hard to have talha winemaking recognised in a similar way.

So back at the Gerações cellar, what does Tina from Florida think of the wine fresh from the talha?

“It’s wine. It’s quite good. And it works. Every time.”

Too many clay pot stories for one post! Next week we continue on the talha trail as I meet a Georgian from the cradle of wine, talk to the talha mafia and wonder why South Africa’s biggest sparkling winemaker is experimenting with amphorae.

Hi Alistair,

Imagine my delight when I tuned into Radio 4 on Tuesday evening around 10.30. They started to talk about wine and Portugal, then low and behold “ here is Alistair Leathhead with the report I was so happy to hear you 😀 mind the presenter then said after the piece “that was Andrew Leathhead from Alentejo. I did shout at her for getting you name wrong. Still loving your great blogs. Have a super weekend. With love Annie x (Hodgson)