So where did it all begin? Who had the crazy idea of growing grapes and turning them into booze?

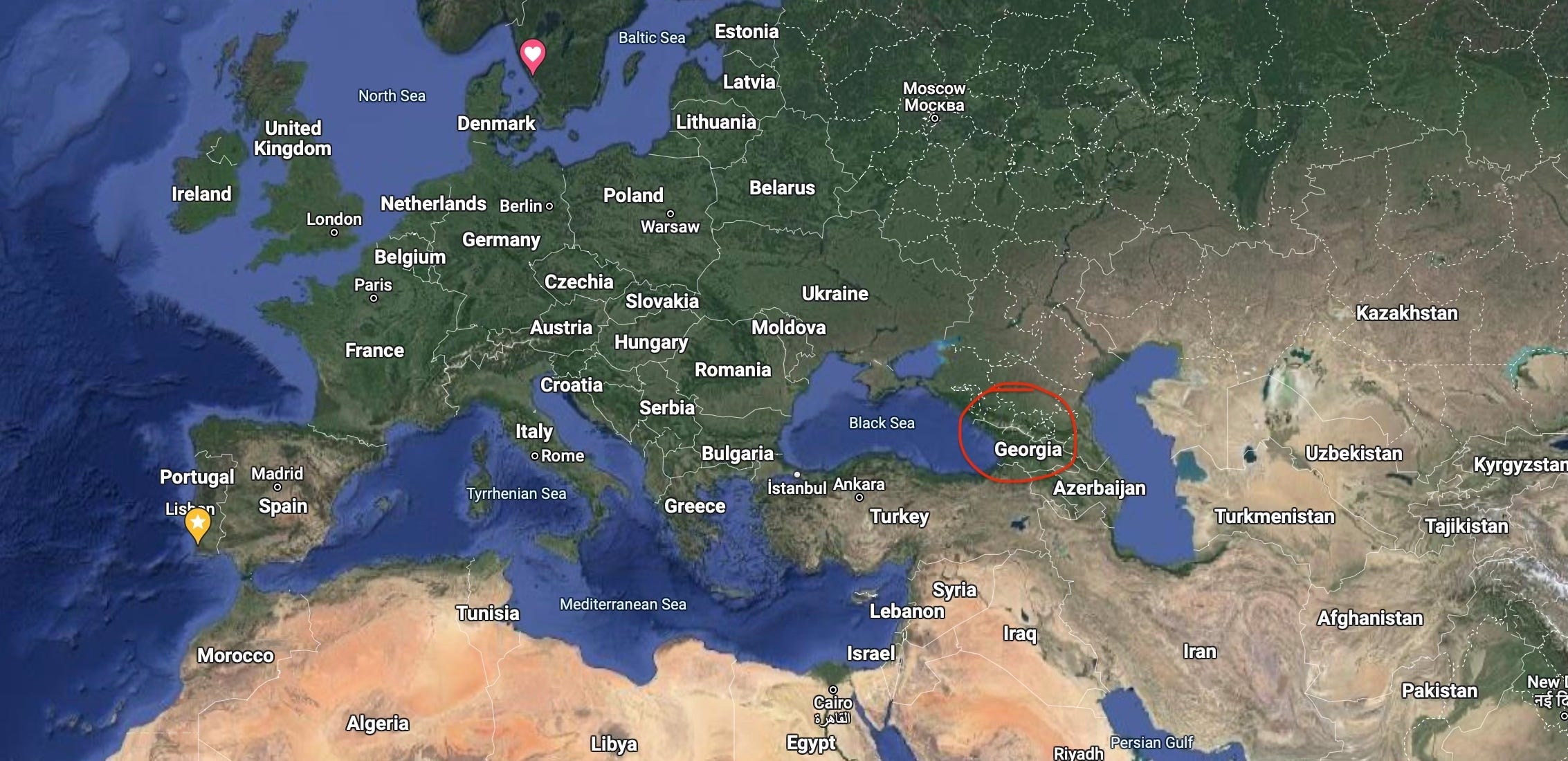

It turns out it all started about eight thousand years ago in Georgia – not the American state but the eastern European country in the Southern Caucasus.

Naturally this is a difficult fact to check, but the nice Georgian winemaker I met at Rocim winery’s amphora day which fell on the celebratory wine-opening St Martin’s Day weekend was pretty convinced.

“It’s proven by UNESCO and we found 8,000 year old seeds which was the final proof. To be fair, the whole Caucasus was the cradle of wine – at the time there were no country limits – this is a fact and we have a lot of archaeological proof,” said Patrick Honneff from Château Mukhrani.

And what did they use for making and storing the wine? Clay amphorae of course: talhas as they’re called in Portuguese, or quevri in Georgian.

I took a couple of his free samples and decided not to argue, checking afterwards that indeed Georgia considers itself the “cradle of wine” kind-of confirmed by Wine Folly who did a deep dive on the issue.

The wine was great – similar to Portugal’s talha wine but made differently as the quevri jars are buried underground. Patrick agreed the wine was generating a lot of interest in both countries as people rediscover old ways of making wine.

“But here in Portugal it’s a real tradition – it’s what is shared with Georgia – it is a real tradition and we are happy that others discover this way of making wine,” he said.

The Amphora Wine Day at Herdade do Rocim was packed with producers from all over the world and plenty of thirsty tasters.

Increased interest in natural wines has helped talha’s rise as a “low-intervention” wine using natural yeast and filtration.

“The wine is really different from a conventional wine, it’s a wine that really reflects the terroir of this area,” said Pedro Ribeiro, the winemaker and general manager of Rocim.

“It’s all about an authentic product. It’s a niche wine of course which is almost impossible to scale – one vessel can make one wine per year and it’s a unique wine with a lot of stories to tell.”

The Ukrainian wine buff Jenia, who we’d met earlier in the year when she’d just arrived from Kyiv and who featured in a previous blog, was pouring Ukrainian amphora wines and preparing to leave Portugal for...Georgia...for a job in the industry there.

She left with huge gratitude to Rocim winery and all the team there for giving her and the family somewhere to stay and a job in a new part of the wine world as war descended on her home.

Our friends at Howard’s Folly had produced a talha wine for the first time, and amid the wine tasting and the sampling of traditional Alentejo food, a group of Cante Alentejano singers and traditional guitarists were milling in the crowd.

There was amphora wine from Italy and Spain, France and even Cuba...(the nearby town, not the Caribbean island with which it apparently provided a name!).

And then I stumbled across Graham Beck wines from South Africa.

We’ve spent a lot of time visiting vineyards and have winemaker friends in the Western Cape, and know Graham Beck as probably South Africa’s most prominent producer of sparkling wine.

“So is Graham Beck now making talha wine?” I cheekily asked the man in the shorts and the Hawaiian shirt who turned out to be Pieter “Bubbles” Ferreira, the company’s chief operating officer.

The short answer is no, but they have an extremely fun sounding R&D unit trying different things in different parts of the world, and it seems there are promising signs for amphorae use in méthod cap classique (MCC) wines.

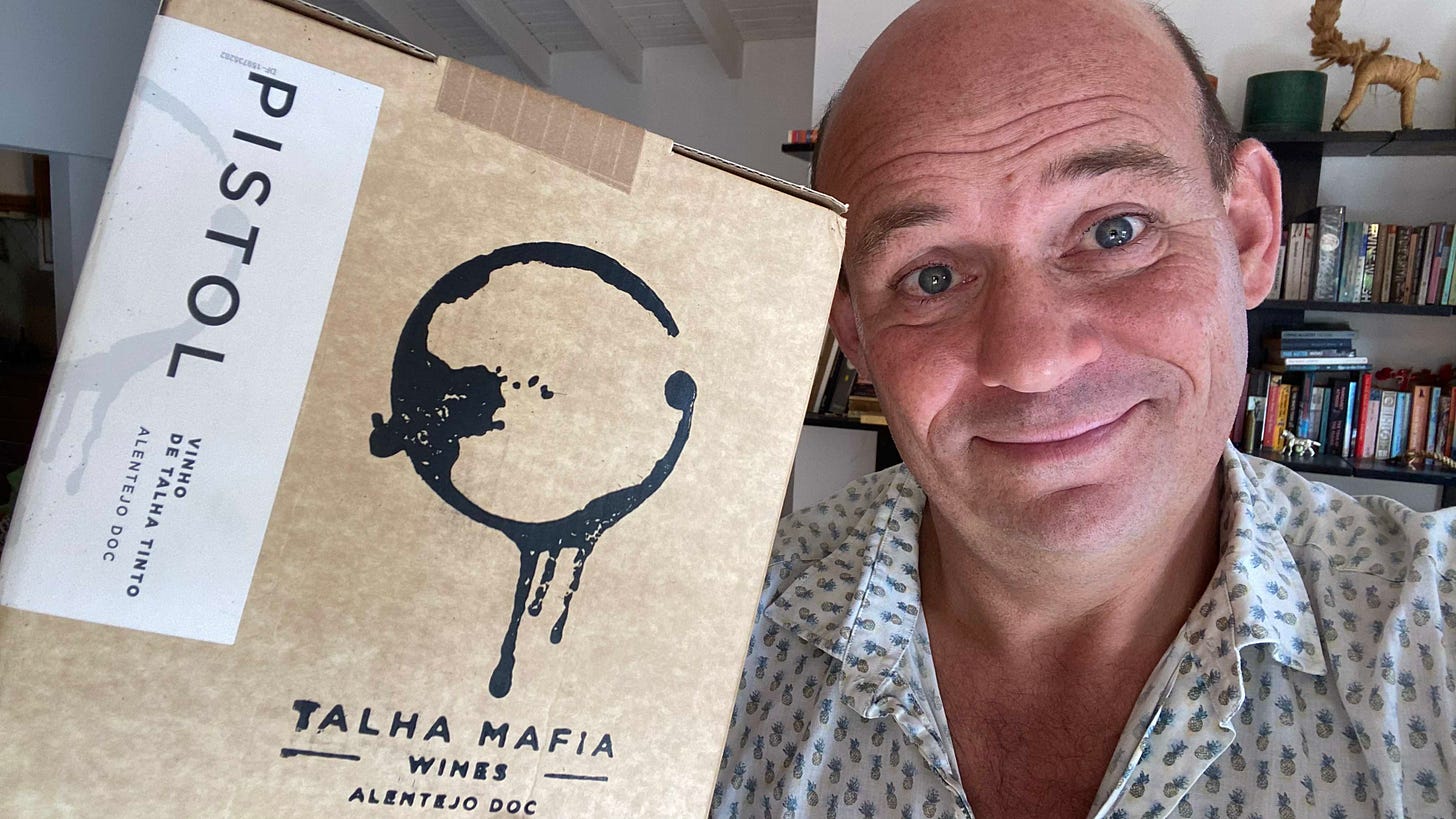

Wandering the hall with a glass I came across the Talha Mafia – a new company based in the talha town of Vila de Frades which I wrote about last time, with a fun logo and a fresh approach to Roman-style wines.

“The project was born four years ago when one of our friends bought this adega in Vila de Frades – a cellar with 12 amphorae,” said Joel Marques – one of the six childhood pals who created the company.

They realised they had something unique, started making “drinkable” wine for themselves and then created a name based on their little ‘mafia’ complete with a bullet hole/wine glass logo and names like Pistol and Revolver.

To them “the world of wine is making experiences and breaking the rules sometimes – respecting the heritage – but breaking the rules,” he said.

One of those broken rules was selling premium talha wine in a box – a well-designed, elegant-looking three-litre container...but still very much a box of wine.

“In Portugal people look to the bag in box like it’s not such good wine, but it doesn’t have to be like that; and we have a concern about sustainability of the planet and so this is reducing the carbon footprint, so we thought why not?”

I’ll definitely be getting back onto that subject in the weeks ahead as I learn more about glass bottle shortages, the high environmental cost of recycling and the possible move towards box wine and even keg wines...more to come!

One of the highlights of our immersive weekend of amphorae wines was meeting winemaker Hamilton Reis at his home in Vidigueira.

We were taken along to his wine cellar basement by Teresa Caeiro, whom I’ve written about, to hear him talk about his take on talha...which is slightly different to most.

Hamilton Reis is one of the big names in Alentejo, having been winemaker at the Cortes de Cima winery for years until moving to Mouchão – the place all the top winemakers have told us to go as we’ve been doing interviews for the podcast (and somewhere we’re hoping to head to very soon).

It took him 15 years to collect all his talhas and one of them has 1675 inscribed on the side – the date it was made.

One of the big problems facing talha winemakers is getting hold of the vessels...as nobody has made them here in a hundred years and the local knowledge has been lost.

“I use a technique that was forgotten, which is fermentation with no skin contact so the wines are open and lighter,” Hamilton Reis said of his process.

He crushes the grapes underfoot for two or three days and as soon as fermentation starts he presses the juice into the amphorae, so the wine isn’t as heavy or earthy.

“I’m replicating a technique of a very old person I met in Portalegre many years ago. His wine was fresh and vibrant and full of fruit and I loved it.”

For the old winemaker it was simple maths – by removing the skins he had more room in the amphora to produce more wine – but it also changed the character of the finished product.

And last, but not least, after multiple tastings and outstaying our welcome, we hitched a lift with Pedro Bonito, who turned out to be sommelier at the nearby Quinta do Quetzal winery and restaurant, and their head chef João Mourato.

We decided to treat ourselves to a lovely lunch the next day amid their vineyards and weren’t disappointed with the menu.

We started with a glass of Quetzal Brut espumante, shared river crayfish, duck and tempura green beans for starters with the estate’s Guadalupe Winemaker’s Selection Antão Vaz white, and then enjoyed a main of roasted Alentejo pork neck with a glass of the blended Guadalupe Winemaker’s Selection red.

That left us well set up for an afternoon of talha tasting and we even took a couple of cases of wine home, as you do.

We’ll be heading back to Vila de Frades, Herdade do Rocim and Quinta do Quetzal next year, that’s for sure, and now we know the lay of the land we may even take a few friends!